Bridging Our Past, Uniting Our Future:

One Community, One People, One History

Gather with us

Tuesday, September 17th at 3:15 pm

At Mechanics Park in Biddeford

on the corner of Main and 45 Water Street

Join us in commemorating the 100th anniversary of the heroic people from the Twin Cities who disrupted the Ku Klux Klan’s attempt to parade across the Biddeford-Saco bridges. Presentation scheduled to begin at 3:30 pm.

Schedule of Events

3-3:15 pm – Local and state dignitaries, from the past and present, will gather at designated meeting points on both sides of the bridge for a symbolic walk of unity.

3:15 pm – The walk to the Main Street bridge will start and will be concluded by a ceremonial handshake between the mayors of Biddoford and Saco. There will then be a collective walk to Mechanic Park in Biddeford.

Walkers from both sides will meet in a symbolic sign near the

3:30 pm – The formal program will begin with Master of Ceremonies, Jason Cote, a teacher at Thornton Academy. Mayor of Saco, Jodi MacPhail and the Mayor of Biddeford, Martin Grohman, will deliver joint proclamations. Anatole Brown, Archivist and Historian at the Saco Museum and Dyer Library, will present a brief historical overview of the 1924 events. Reza Jalali, an acclaimed educator and advocate, will provide the keynote address, focusing on the ongoing need for inclusivity and unity, as well as rooting noting the similarities between rhetoric of the past and present. The event will conclude with a musical performance by the Alumni Band. The ceremony and presentations will be brief, impactful and meaningful.

This event will be held rain or shine.

RULES OF THE ROAD

There will be no road closure for this event. Everyone is invited to meet directly at Mechanics Park.

Due to safety concerns a small select group of participants will walk and meet on the bridge.

All those walking will be expected to follow the following rules:

Walkers will be led by volunteers wearing fluorescent vests and followed by a volunteer.

Walking will be on the sidewalk only.

Care must be taken at the crosswalk and should be done only when directed to do so by volunteers when the crossing signal is flashing and all traffic has stopped.

It make take several cycles for all to cross safely.

Walkers will then proceed together to Mechanics Park.

For more information:

info@biddefordcultural.org

207-283-3993

A Brief Lesson In History

September 1, 1924

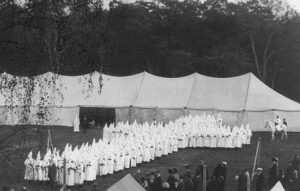

One hundred years ago, on September 1st, 1924, the Ku Klux Klan held a Labor Day Parade in Saco. They paraded down Main Street in Saco, many wearing the easily recognized KKK garb, but some paraded only donned with the headpieces, and some, without any head pieces at all. It was reported to the citizens of Biddeford that the Klan wanted to parade across the bridges into Biddeford.

At that time, the KKK was very active in the State of Maine and at its peak, their membership grew to over 150,000. This membership was among the largest in the country. The larger groups were found in the communities of Portland, Lewiston, and Brewer, but they were not limited to those areas. The first Klan parade in the State of Maine was held in Milo, Maine on Sept 3, 1923, a small town in Piscataquis County which had a population of about 1100 people.

Since Maine was not a diverse state in the 1920’s, rather than focusing on African Americans, the Maine Klan primarily targeted immigrants and Roman Catholics, including Irish, Canadians, and Jewish community members. These ethnic and religious groups were deemed inferior to the middle-class Protestant citizens who considered themselves to be “true Americans.”

Initially, the Ku Klux Klan was formed after the Civil War to prevent freed slaves from gaining political power and integrating into white American society. The growth of the Klan in Maine was, in part, a revival of old divisions which began in 1843 with the political “Know Nothing” movement in New York. This Nativist movement focused on Irish and German Catholics whom they felt couldn’t be loyal to the United States, because they were under the control of the Pope.

Between the years of 1850-1930, millions of new immigrants came to the US in hope of better lives and opportunities. These immigrants took jobs in the textile mills and on the farms and included French Canadians, Italians, Poles, Greeks, Lithuanians, and others, many of whom were Catholic or members of Jewish communities. Most did not speak English. They started their own churches and schools in a desire to maintain their cultures, languages, and traditions, and these actions made assimilation with the general public more difficult. The failure and refusal to assimilate was considered a threat to the country by many of the white Americans in communities throughout the United States. The Klan, in the 1920’s, was revived and grew with a focus of “what made one an American.” The Klan did not define or consider these immigrants as being Americans or as belonging in this country.

Eugene Farnsworth of Maine was a charismatic speaker and became King Kleagle of the Klan. Much of the growth and success of the Klan in Maine can be attributed to him, as he spurred its growth in the state. The Klan in Maine focused on fraternal rites, parades, and political campaigns to spread their message. In 1924, the Klan backed Republican Ralph Brewster who was running for governor. It is not clear that he was a member of the Klan, but he was supported by them. He was elected Governor in 1924, and this was considered a Klan victory. The Klan backed many others running for office to accomplish its goals. Their agenda included stopping state funding for parochial schools, requiring that students read from the Protestant Bible in school, and requiring that the only language spoken in schools was English. The Klan targeted Catholic groups and figures such as the Pope, Jesuits, and the Knights of Columbus. They did not want Catholics and Jews on public school boards.

In some cities there was strong opposition to Klan activities, particularly by Catholics. This happened in Biddeford on the fateful day, September 1st, 1924, and in the weeks leading up to it.

In 1924, a Labor Day parade of Klansmen was organized to start in Saco with plans to parade down Main Street in Saco, to Main Street in Biddeford up to Biddeford City Hall, and they would return to Saco by use of the Elm Street bridge. Word of this became public, and articles were placed in the Portland Evening Express and Biddeford Journal, as well as La Justice, a Biddeford French newspaper. Tensions were running high on both sides of the bridges.

Mayor John Smith of Saco was quoted as saying “ If the young roughneck crowd from Biddeford comes over and attempts to start anything, they will get what is coming to them. If this crowd of Biddeford roughnecks stays home, there will be no trouble.” The next day, Mayor Edward Drapeau, the son of Canadian immigrants, replied to this comment in the Biddeford Journal. Here is part of his response:

“The young citizens of Biddeford have never appeared in gangs with masks to conceal their features and to my knowledge they have never gathered themselves together for the purpose of organized intimidation, if not violence. For my own part, I wish to warn the Kluxers and their friends to remain in the friendly precincts of Saco on Monday, September 1st, and at all times thereafter. I intend to use all resources at my command to prevent this lawless organization of the forces of bigotry and ignorance which unfortunately exists in our neighboring communities from inciting acts of violence in this city.”

Mayor Drapeau condemned the Mayor of Saco for allowing the KKK to parade. He ordered the Chief of Police of Biddeford to have a special force at each bridge to stop the parade if they tried to enter Biddeford. This was all printed in the newspaper. The next day, the Portland Press Herald wrote that the Klan stated they never intended to cross into Biddeford.

Thousands of Klan supporters were expected to attend, but only about 300 showed up to march, some in costume and some without their robes and hoods. Many people lined their route, some in support and others to vilify them in an early show of unity and community. Stories reveal that the Irish of Biddeford banded with the Franco-Americans and blocked the Bradbury Bridge, on Elm Street, while the Franco’s blocked the Main Street Bridge by Factory Island. They were armed and ready to defend their rights and city against the Ku Klux Klan. Saco constables were guarding the bridges at Elm Street and York Hill. They prevented the marchers from crossing into Biddeford. The Irish and the Franco-Americans were waiting for them on the other side, armed with rocks and bricks, daring them to cross into their city. The angry Irish and Franco-Americans, defending their city, were enough to prevent the Klan from attempting to cross the bridges, and they turned in retreat.

There were heroes on both sides of the river, on that day, men and women who believed that there was no place in America for racial, religious, and ethnic hate. Because of the actions of such individuals, in Biddeford and Saco, the Klan lost its appeal, membership declined, and the organization disappeared from our communities.

After this incident, there seemed to be a change in the culture of the cities of Biddeford and Saco, and its citizens, with more understanding and cooperation noted amongst the various ethnic groups and community. We have come a long way in 100 years, but there is still more work to be done.

Photo on the left is courtesy of Saco Museum, taken in 1925 in Saco, ME.

Photo on the right is from the National Archives and was taken in Portland, ME.

The info below comes from The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine

Maine History Documents 2019 History of Maine – The Rising of the Klan by Raney Bench Special Collections

“The last words on the rise and fall of the Klan on MDI to one with first-hand knowledge who lived here. Ray Foster, a local plasterer and contractor, delivered this account to Island historian Bob Pyle in 1974:

“The Ku Klux Klan was active then [1928] and a lot of us joined it thinking it was kind of like a cross between the Masons and the Boy Scouts. We liked the encampments [at what is now Barcadia near the Trenton Bridge]. . . . It wasn’t long before we were told we had to hate black people. We weren’t excited by that, but there weren’t many blacks around MDI then, so it didn’t make much of a practical difference. Besides, society was different then. Next, we were told we had to hate Jews. Guys started to get uncomfortable, then. There weren’t many Jews around but there were people like Dan Rosenthal, a peddler who came in summer. Everybody liked Dan. He was a good man.

Then we were told we had to hate Catholics. Well, that did it. There were a lot of Catholics around. We knew damned well they were good people. A Catholic priest in Northeast— Father Kinney—was active in the fire company, for example. There was a Catholic church on Lookout Way in Northeast Harbor. The Catholic church had just bought one of the old local houses on Summit Road and was renovating it for a rectory. The Catholic church was enlarging that story-and- a-half little house into a larger three-story rectory.

Well, just about all the workmen in Northeast Harbor donated at least a day’s work on that rectory job and we all signed our work. That was our message to the Ku Klux Klan, from every damn one of us. You’ll find our signatures all over that house. That was the end of the KKK for Northeast Harbor.”

November 21, 2013.

A COLLABORATIVE EFFORT

between the people of Biddeford and Saco